Synoptic problem

The synoptic problem concerns the literary relationships between and among the first three canonical gospels, those of Mark, Matthew, and Luke. These are known as the Synoptic Gospels (from the Greek 'syn,' meaning "together," and 'optic,' meaning "seen"). Similarity in content, word choices and event placement indicates some kind of literary interrelationship.

The synoptic problem concerns how this interrelation came to be and the nature of the interrelationship itself. Any solution must account for the similarities and differences in content, order, and wording. Possible solutions speculate either a direct relationship (one Evangelist possessed one of the gospels) or indirect (two Evangelists having access to a shared source). The sources may be written or oral; single or multiple. In some sense, the synoptic problem is analogous to the alleged problems in Hebrew Bible scholarship that led to the Documentary Hypothesis.

Contents |

Literary phenomena in the synoptic gospels

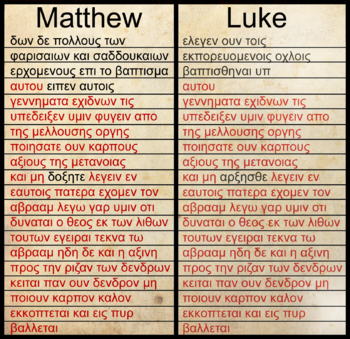

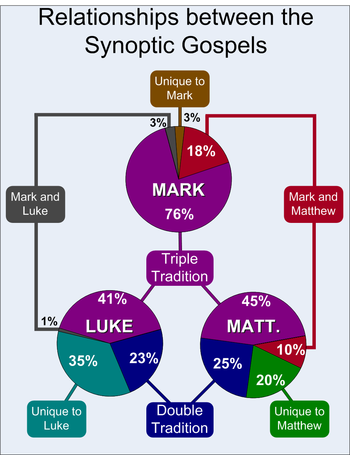

Eighty-nine percent of Mark's content is found in Matthew, and seventy-two percent of Mark is found in Luke.[2] The material in common to all three constitutes the Triple Tradition. The Triple Tradition is largely narrative but contains some sayings material. Since so much of Mark is Triple Tradition, some scholars combine it with the rest of Mark and talk about a Markan Tradition instead. In addition to the Triple Tradition, Matthew and Luke share content not found in Mark, called the Double Tradition. This content is mostly composed of sayings (mainly by Jesus, but some by John the Baptist) but includes at least one miracle story (the Centurion's Servant) as well. Text in common with Matthew and Mark or Luke and Mark is also referred to as the double tradition. Matthew and Luke both have material of their own not in common to either of the other two Gospels, called Special Material which are a considerable portion of the Gospels.

Agreement in the order of the content is the strongest indication of a documentary dependence, especially when the agreement touches topical arrangements instead of chronological (e.g., both Matthew and Mark relate the death of John the Baptist in a flash-back). Therefore most scholars have not found purely oral theories plausible. The pattern of order is quite different between the Triple and Double traditions.

In the Triple Tradition, the order of the pericopes (sub-sections) is largely shared between Matthew and Mark or Luke and Mark or among all three. It is rarely the case that Matthew and Luke agree against Mark in arranging the Triple Tradition. This formal property means that Mark is a middle term between Matthew and Luke. Specifically, the following scenarios are logically possible:

- Indirect relationship. If Matthew, Mark and Luke are independent revisions of a common source, then this ur-gospel in order is best represented in Mark. In fact, this ur-gospel can be thought of as an Ur-Marcus. (Lachmann 1832; Holtzmann 1863).

- Direct relationship. Butler showed that Lachmann's conclusion does not hold up if any gospel is directly related to another. He found that three (later expanded to four by Farmer 1964) situations were possible:

(1) Mk (2) Mt (3) Lk (4) Mt Lk

/ \ Mk Mk \ /

Mt Lk Lk Mt Mk

|

- Legend:

- (1) Markan priority. Matthew and Luke copied Mark in Triple Tradition. (Two-Source Hypothesis, Farrer Hypothesis)

- (2) Matthean priority. Luke copied Mark who copied Matthew who was first (Augustinian hypothesis)

- (3) Lukan priority. Matthew copied Mark who copied Luke who was first (Few adherents).

- (4) Markan posteriority. Mark conflated Matthew and Luke (Griesbach Hypothesis)

There is an additional fact about the arrangements of the Triple Tradition: Mark's order is almost always supported by either Matthew or Luke. This lends strength to the Griesbach Hypothesis [scenario b(4)], but that support is weakened by Tuckett's mathematical observation that the relatively rare deviations of either Matthew or Luke from Mark's order means that this observation is not statistically significant. Tuckett's model may be criticized for assuming randomness on part the later redactors (departures from a source are equally likely), but since Matthew's deviations are toward the beginning and Luke's are towards the end, it is not surprising that both Matthew and Luke rarely re-ordered the same Markan pericope.

The agreement in order within the Double Tradition, however, is much weaker, mostly in the Sermon on the Mount/Plain, leading scholars to favor an indirect relationship for the Double Tradition. Thus, Matthew and Luke copied independently a sayings collection called Q. On the other hand, there is enough order in Q to argue that Q is a documentary source. Those other theories which do not hypothesize a shared sayings source usually assume that Luke copied the Double Tradition from Matthew.

A close comparison of the wording within the Triple Tradition shows that Matthew and Mark are usually quite close, with Luke being somewhat further. To the extent that Luke agrees in wording at all with the other two, it usually is with both or with Mark. Luke's agreements with Matthew against Mark, the minor agreements, are less frequent but not insignificant.

The role of the minor agreements is significant in as much as they suggest that Luke and Matthew might not be independent from one another. However, culminating in 1924, Streeter was able to show, to the satisfaction of most of the scholars of the time, that these "minor agreements" are largely trivial, coincidental, or attributable to textual corruption. Streeter's work allowed the Oxford School to replace the Ur-Markus of Holtzmann's 1863 Two-Source Hypothesis with the canonical Mark.

Griesbach's explanation of Mark's redactional procedure predicts that Mark should more agree with the Evangelist he currently is copying. Overall this is true, but often Mark prefers Matthew in areas he should be more like Luke.

As with other ancient texts, the fact that Mark's wording is usually fuller than either Matthew's or Luke's can be taken as buttressing either the priority or the abridgment arguments. In the priority perspective, the later writers simplified Mark's narration in their borrowing; in the abridgement argument, Mark would have amplified the other writers. Mark is also felt by some to be more "primitive" than either Matthew or Luke, thus arguing for priority, though there are also arguments for Matthean priority (e.g. being more Jewish), or that if Mark were editing two gospels together, his Greek might become more choppy and poor. This area of the synoptic problem has thus been riddled with reversible and inconclusive arguments, illustrating the often subjective character of such interpretations.

Proposed solutions

This section is a brief overview of current speculative solutions to the Synoptic Problem including scholarly thought first proposed in the 1800s and traveling back through traditional church history and church views citing the writings of the ancient church fathers. Most modern study focuses on the two-source hypothesis and on the two-gospel hypothesis. Most modern scholars hold to one of these two views, with the majority (though not a consensus) holding to the two-source hypothesis.[3][4] Unlike the two-source hypothesis, the two-gospel hypothesis concludes that the traditional accounts of the gospels (order and date of publication, as well as authorship) are mostly accurate.

| Part of a series on |

| The Bible |

|---|

|

| Biblical canon and books |

|

Old Testament (OT) New Testament (NT) Hebrew Bible Deuterocanon Antilegomena Chapters and verses |

| Development and authorship |

| Jewish canon Old Testament canon New Testament canon Mosaic authorship Pauline epistles Johannine works Petrine epistles |

| Translations and manuscripts |

| Septuagint Samaritan Torah Dead Sea scrolls Masoretic text Targums · Peshitta Vetus Latina · Vulgate Gothic Bible · Luther Bible English Bibles |

| Biblical studies |

| Dating the Bible Biblical criticism Higher criticism Textual criticism Canonical criticism Novum Testamentum Graece Documentary hypothesis Synoptic problem NT textual categories Historicity

Internal consistencyPeople · Places · Names Archeology · Artifacts Science and the Bible |

| Interpretation |

| Hermeneutics Pesher · Midrash · Pardes Allegorical interpretation Literalism Prophecy |

| Perspectives |

| Gnostic · Islamic · Qur'anic Christianity and Judaism Biblical law

Inerrancy · Infallibilityin Judaism · in Christianity Criticism of the Bible |

|

· |

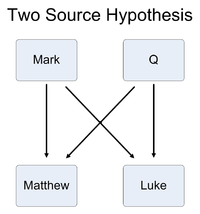

- The two-source hypothesis states that Matthew and Luke independently copied Mark for its narrative framework and independently added discourse material from a non-extant sayings collection called Q. Much work has gone into the extent and wording of Q, particularly since the discovery of the Gospel of Thomas which attests to the sayings gospel genre. Holtzmann's 1863 theory posited an Ur-Marcus in the place of our Mark, with our Mark being a later revision. Some scholars occasionally propose an unattested revision of Mark, a deutero-Mark, being the base of what Matthew and Luke used. In 1924 Burnett Hillman Streeter further refined the Two-Source Hypothesis into a Four-Source Hypothesis, with an M and an L being a unique source to Matthew and Luke respectively, with Q and L combined into a Proto-Luke before Luke added Mark. While unique sources, such as M, L, or Semitic first editions, are interesting for form-critical purposes, they are quite peripheral to the Synoptic Problem as to how the canonical gospels are interrelated.[5]

- The two-gospel hypothesis (once called the Griesbach hypothesis) states that Matthew was written first (probably in the 40s AD by the apostle Matthew), while Christianity was still confined to Judea, to calm the hostility between Jews and Christians. After Matthew, as the church expanded beyond the Jewish world, Luke was written as a gospel to the Gentiles by Luke the Evangelist, probably in the 50s AD. But since neither Luke (nor his patron Paul) were eyewitnesses of Jesus, Peter gave public testimonies that validated Luke’s gospel. These public speeches were transcribed by Mark the Evangelist into Mark’s gospel and distributed immediately thereafter, as recorded by the early church father Irenaeus. Mark's shorter and less-polished nature is therefore a consequence of the fact that it came from a series of transcribed speeches that were never meant to be a separate gospel tradition. Paul then allowed Luke’s gospel to be published.[6] This hypothesis is the most serious alternative to the two-source hypothesis.[7][8] Its main advantages over the two-source hypothesis include the fact that it relies not just on internal evidence, that it doesn’t require lost sources or other “plugs” (like the Q document) and that it reconciles the view of the early church with the evidence.

Other proposed solutions

- The Farrer hypothesis posits that Mark was written first and Matthew used Mark, but that Luke used both, thus dispensing with Q.

- The three-source hypothesis (e.g. Simons 1880; Morgenthaler 1971) holds that Matthew used Mark and a written sayings source, whereas Luke used both of these as primary sources, plus Matthew as a subsidiary source. The sayings source of this hypothesis is therefore not necessarily identical to Q.

- The Augustinian hypothesis holds that Matthew was written first, then Mark, then Luke, and each Evangelist depended on those who preceded him. This position is in the closest agreement with church father testimony of the gospels' origins. John Wenham was considered one of the prominent contemporary scholars who supported the Augustinian hypothesis. A variant of this hypothesis that was popular mainly among Roman Catholic scholars in the first half of the 20th century was that Matthew was written first, and copied by Mark and then Luke, but that Matthew was written in Aramaic, and when it was translated to Greek the translator liberally adapted some of the phraseology of the other gospels which were already in Greek. Some scholars argue that the Griesbach hypothesis is merely another variant of this original hypothesis since they agree on their principal points.

- The Parker hypothesis (Parker 1953) argues that a proto-Matthew, probably written in Aramaic, in addition to Q, was written first. Mark would have followed proto-Matthew and added new elements of his own. It is argued that a Greek translator would have fused elements from Mark, proto-Matthew, and Q in order to create a Greek Matthew close to the version we know. Independently, Luke would have written his gospel with these sames sources (Mark, proto-Matthew, Q) added with other sources known by John, which would explain why Luke is the closest of the first three gospels to John.

Other theories usually posit more hypothetical and proto-sources. For example, Marie-Émile Boismard calls for seven hypothetical documents, one of them a form of Q.

A handful of researchers, such as Eta Linnemann (a former student of Rudolf Bultmann and Ernst Fuchs),[9] argue that each of the evangelists are independent of one another and that the apparent literary similarities are merely coincidental. This theory is in the character of the "dictation" theory that the whole Bible, including the Gospels, was dictated by the Holy Spirit and therefore no intermediate or source documents between books required. This theory is contradicted by Luke's affirmation that he used sources when writing his history of Jesus (Luke 1:1-3), and is quite different from the Evangelical understanding of plenary verbal inspiration.

See also

- Gospel harmony

- Two-source hypothesis

- Q document

- Common Sayings Source

- The Secret Gospel of Mark and the Synoptic Problem

References

- ↑ Matt 3:7-10 & Luke 3:7-9. Text from 1894 Scrivener New Testament

- ↑ Honoré, A. M. "A Statistical Study of the Synoptic Problem." Novum Testamentum 10 Aug.-July (1968): 95-147. On page 96 Honoré compares the similarities between the three Gospels with the number of words in common.

- ↑ Black, David (2001). Why Four Gospels?. Kregel Publications. ISBN 0-8254-2070-9

- ↑ Beck, David (2001). Rethinking the Synoptic Problem. Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-2281-9.

- ↑ Daniel Gaztambide, "The Synoptic Problem: Two-Source Hypothesis and Q", AramaicNT.org, accessed August 19, 2006.

- ↑ Black, David (2001). Why Four Gospels?. Kregel Publications. ISBN 0-8254-2070-9

- ↑ Black, David (2001). Why Four Gospels?. Kregel Publications. ISBN 0-8254-2070-9

- ↑ Beck, David (2001). Rethinking the Synoptic Problem. Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-2281-9.

- ↑ Eta Linnemann, Is There a Synoptic Problem: Rethinking the Literary Dependence of the First Three Gospels, trans. Robert W. Yarbrough (Grand Rapids: Baker), 1992.

Further reading

- B.H. Streeter, The Four Gospels. A Study of Origins, Oxford 1924.

- H.C. Thiessen, Introduction to the New Testament, Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids 1976, ss. 101-161.

- A.H. McNeile, An Introduction to the Study of the New Testament, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1955, pp. 59-91.

- E. Linnemann, Is there a Synoptic Problem: Rethinking the Literary Dependence of the First Three Gospels. Translated by Robert W. Yarbrough. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1992. Originally published as Gibt es ein synoptisches Problem? (Neuhausen: Hänssler, 1992).

External links

- Synoptic Problem Homepage: analysis of the various theories that have been proposed, bibliographical information, articles.

- 1,488 solutions to the Synoptic problem

- Synoptic Gospels Primer: introduction to the history of literary analysis of the Greek gospels, and aids in confronting the range of factors that need to be taken into consideration in accounting for the literary relationship of the first three gospels (by Mahlon H. Smith)

- The Synoptic Problem: A general overview by Daniel B. Wallace.

- Five Gospel Parallels

- A statistical approach to the synoptic problem

- Synoptic gospel sources: A presentation of the three-source hypothesis.

- The Synoptic Problem: Two-Source Hypothesis and Q: Introductory article to the Two-Source hypothesis (Markan Priority) and Q Theory, including case studies and bibliography.

- Another study of the Synoptic Problem.

- The Lost Gospel of Q - Fact or Fantasy? by Eta Linneman, PDF, 67 KB.

- The Importance of the Synoptic Problem for Interpreting the Gospels by Allan J. McNicol